September 1, 2025

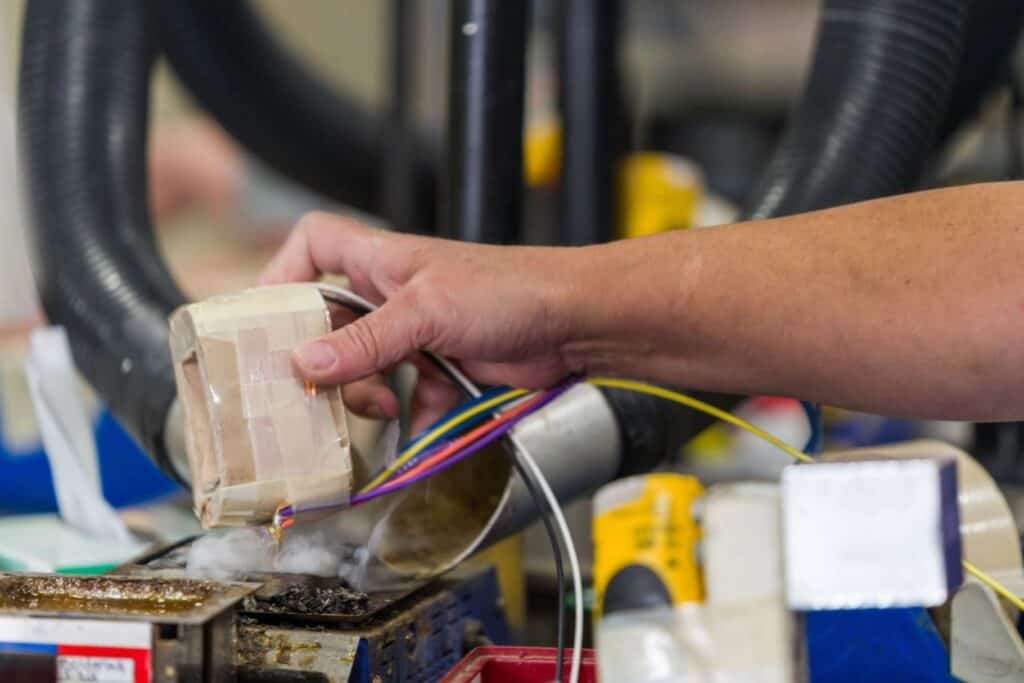

ANTIGO – For more than nine decades, President/Owner Julie Berndt said Johnson Electric Coil Company has built a legacy of excellence – evolving from a small, family business into an innovative manufacturer of custom transformers and inductors.

The Antigo-based company has been under her leadership since 2022, Berndt said – the culmination of a career that saw her move from the company’s front-desk receptionist to its first-ever female president and owner.

It’s “pretty amazing,” she said, for any company to be operating into its 91st year – crediting its longevity to the caliber of workers in an area known for its manufacturing prowess.

“[Johnson Electric Coil] Company ended up coming here, I believe, in the 1970s,” she said. “They actually started in Illinois, and the reason they came here is because of the work ethic.”

Berndt said she’s been “very blessed” with a remarkably reliable and talented crew of 55 employees.

“I always tell everybody, hands down, I’ve got the best group ever,” she said.

Recognizing that there’s a limited pool of local workers, Berndt said Johnson offers highly competitive wages and benefits, while also fostering a maximally respectful environment.

“I have some very candid conversations with my employees, and I think [the key to retention] is the way they are treated,” she said. “It is the empowerment they have out there. They are not micromanaged. I mean, all these ideas for changing things and making [our operations] better are 100% their ideas. I think that says a lot, because they feel [a sense of] ownership of this company.”

Berndt said the company’s culture is embodied in its slogan: “Unified, Unselfish, Single-Minded.”

“From me, all the way [through the process] until that transformer gets out the door and every hand that touches [it], I feel we all have the same mindset of serving our customer: doing the best we can, unselfishly,” she said.

Johnson’s customers, Berndt said, receive price quotes within 24 hours, while also benefiting from constant communication and updates.

She said she takes the resulting positive feedback to heart and provided a recent example from a customer.

“He said, ‘Julie, you have no idea – we actually sleep at night, because we don’t have to worry about transformers,’” she said. “That is a huge compliment.”

Thorough customer focus, continuous improvement and a devoted team, Berndt said, are central factors for Johnson’s perseverance in a market where other competitors continue to close.

The other crucial component, she said, is the company’s ongoing investments.

One of its largest in recent history, Berndt said, was a significant investment in Johnson’s capabilities to produce larger transformers.

Previous capabilities, she said, saw Johnson maxing out at 300-kVa transformers, but the company can now produce 1,000-kVa transformers right in Antigo, with some “as tall as six feet.”

This initiative, Berndt said, is in response to a trend of American companies ordering smaller transformers from China and other countries.

“Typically, you’re not going to send a 1,000-kVa [transformer] overseas – it’s too big and it’s too costly,” she said. “We feel getting into this market with the larger [transformers] is something that’s going to be very beneficial.”

And Berndt said thanks to these investments in Johnson’s capabilities, the company is fully charged for an electrifying future.

An unexpected climb

Berndt said her path to the top at Johnson was anything but traditional, and she credits her natural friendliness for helping her succeed in an industry that used to be exclusively about the “nuts and volts.”

It all started, she said, when she was 19 years old.

Not feeling like college was the right fit for her, Berndt said she took an office job at Johnson Electric Coil Company, where her then-fiancé worked.

Though she admits she didn’t know much about the company’s products at the time, Berndt said she always knew how to talk to people.

Working the phones at Johnson, Berndt said she instantly enjoyed the conversations she had with customers – though one of her more “old-school” supervisors was not such a fan of her ways.

“He would say to me, ‘You need to not talk to these people – you need to pass these calls on,’” she said. “I can remember trying not to be me, but I can’t help [but be] me.”

Fortunately, Berndt said her talent for talking was also noticed by others.

“The president [of Johnson] at the time noticed I was quite talkative and [how] I was able to build relationships…,” she said. “It’s weird looking back. I was just being me, and I talk – but he saw that as, ‘Oh, that’s pretty interesting – she’s having conversations other than “what do you want to order?”’”

Summarily, Berndt said a new customer service role was created to suit her sociability – sparking a series of growth opportunities that led her to thrive in concert with the company.

Now, some 30 years later, serving as president/owner of Johnson Electric Coil Company, Berndt recently led the business through its 90th year.

Lean, not mean

As her career at Johnson progressed, Berndt said her ability to connect with customers was bolstered by company leadership, who encouraged her to continue her education.

A second try at college, she said, proved more successful, yielding an associate degree, then a bachelor’s and ultimately, a master’s.

Relatively early in her time at Johnson, Berndt said her studies led to a concept that would soon prove invaluable: lean manufacturing.

Working as an operations manager at the time, she said the concept’s importance was driven home when a long-term customer suddenly broke away after his team inspected the Johnson shop where his product was made.

“He said, ‘Julie, we love working with you… but I’m going to be honest with you – we went through your shop, [and] your shop is dirty, cluttered and you don’t work in a very lean manner – there are far more steps [than necessary], which costs money,’” she said.

Sharing this troubling feedback with the then-president, Berndt said she committed to learning more about lean manufacturing and was eventually assigned a new title: lean coordinator.

This position, she said, tasked her with implementing the principles of lean manufacturing, which theleanway.net identifies as:

- Defining value – what the customer is willing to pay for

- Mapping the value stream, wherein activities that don’t add value to the end customer are considered waste

- Creating flow to ensure remaining steps run smoothly, without interruption or delay

- Establishing a pull-based system to limit inventory and work-in-progress items, while ensuring availability of necessary materials and information

- Pursuing perfection and finding ways to improve production and efficiency every day

As promising as these principles sounded on paper, Berndt said putting them into practice led to internal friction.

“First of all, [lean] is a discipline, and people typically don’t like change,” she said of the 2007 implementation. “But in all honesty, our company was not doing very well. We were taking very good care of our customers, but financially, we really were not doing very well, so this change really needed to happen for the company to sustain.”

Still, Berndt said a mixed reaction of support and resistance ensued.

“I remember when I took the position over and I had a few people [say], ‘You don’t know anything about making transformers,’” she said. “And I said, ‘You’re right – I don’t, you do… but I know lean, the mission, the values, the policies, procedures, etc.’”

Lo and behold, Berndt said “we started doing this and started making money – [employees] started getting bonuses.”

As the team bought into lean principles and Johnson’s production and sales increased, she said the company’s outlook was promising – until the Great Recession of 2008.

Berndt said having more than a year’s practice of lean manufacturing at Johnson proved fortuitous during this time.

“If we hadn’t been doing what we had been doing, I don’t think we would have survived the 2008 recession,” she said.

In the years following the recession, Berndt said she continued to climb the ranks, eventually becoming vice president, then president/owner of Johnson, guiding Johnson through a period of rapid growth with doubled production, record sales and strategic reinvestment.

However, the most important result of lean manufacturing, she said, dates back to her initial goal with the company: pleasing the customer.

“The customers expect us to do our best,” she said. “They expect a low-cost product, and the only way we can [achieve] that is from what we can control inside [the facility] – that’s on our end. And that’s what they expect.”

An electrifying future

For a 90-plus-year-old operation well in tune with its past – “this company went through wars, depression, recession, a fire, COVID-19 and survived” – Berndt said conversations about its future are constant.

“We don’t have everything solved, but we know we’re going to keep going and keep progressing, because we are not going to be that company that is just sitting back and not paying attention to what customers’ needs are, or what the markets are drawing to us,” she said. “We’re doing a lot of things here that we feel are going to keep us going. No. 1… is how you treat people – from vendors to employees to customers.”

Oshkosh Corp. renames Defense segment, appoints Nordlund as president

Oshkosh Corp. renames Defense segment, appoints Nordlund as president Three centuries of goodness: Seroogy’s turns 125

Three centuries of goodness: Seroogy’s turns 125