November 16, 2022

KAUKAUNA – UA 400’s 61,000-square-foot training center in Kaukauna and a 5,600-square-foot satellite training center in Fond du Lac are doing what they can to help supply employers with the qualified workers they need.

“If you want a career and the ability to make a livable wage, come check us out” – those are the words of Trevor Martin, business manager at Plumbers & Steamfitters UA Local 400 in Kaukauna.

Serving 18 counties in Northeast Wisconsin, UA 400 is affiliated with the United Association of Plumbers & Pipefitters, which has approximately 355,000 members in the U.S. and Canada.

“We have about 2,400 members in our union,” Martin said. “We’re trying to get in front of as many people as we can to show what we offer. We’re willing to train people – with pay – and then match them with prospective employers who need their services.

He said UA 400’s goal is to match employers and workers specializing in plumbing, steamfitting, HVAC/R service and pipe fabrication.

“We’re the entity that gives employers the confidence to bid on projects,” Martin said.

Who do they work with?

Martin said UA 400 has more than 100 contractors it works with.

“Among them are Georgia Pacific, (Fincantieri) Marinette Marine, Lambeau Field, school districts, healthcare entities, power plants and other paper mills,” he said. “The Georgia Pacific project in Green Bay will have about 300 of our members working there. Marinette Marine is a generational thing – a worker could get trained out of high school and spend their entire working career there. There was also like $2 billion worth of school referendums on the November ballot (which will spark open positions).”

Martin said some of UA 400’s members might work for six different employers a year.

“They can walk from one employer to the next, and their wage rate is the same, their pension contribution is the same, etc.,” he said. “We hash out all the specifics for our members. On the other hand, we have members who’ve been in the trade for 35 years and never left the employer they got their apprenticeship from.”

Dustin Delsman, assistant business manager at UA 400, said sometimes there is confusion in regard to what the union does.

“We have the training facility here and we’re headquartered here, but at the end of the day, Local 400 doesn’t employ our 2,400 members,” he said. “We only employ about 15 people to keep the entity up and running daily. The rest of those members are employed by the contractors – they’re on their payroll and at their disposal. We find the workers and make sure they’re trained. While we’re all one big group, we all have different roles.”

//s3.amazonaws.com/appforest_uf/f1668633358881x738965359869915300/richtext_content.webpTrevor Martin

Because the demand for trade workers continues to impact the industry, Martin said UA 400 is looking at the possibility of filling needed positions from outside the area.

“We’re mostly looking at people looking to stay in Northeast Wisconsin, but we have to think outside the area – especially for pipe fitting,” he said. “We don’t expect anyone to relocate here just to join Local 400 – they need to have an opportunity for solid employment to consider that.”

Martin said the problem isn’t solely about finding workers, it also involves the skill level required to “hit the ground running” to perform jobs.

“We can find entry-level candidates and apprenticeships, but we need more skilled people,” he said. “We produce them, but not as quickly as we’d like, or what employers need. They could take on more customers if they had more qualified manpower – we take that to heart.”

Looking past the short-term

Martin said if prospective candidates are willing to put in the time and look long-term, there are opportunities for “exponential growth.”

“With the shortage of workers right now, you could make $25 an hour driving a forklift,” he said. “That’s a good wage, but our apprentices make $22 an hour their first year. We have to get in front of people and say, ‘How long do you want to drive a forklift for $25 an hour?’ Yeah, (the apprentice pay is) $22 an hour right now, but in five years, it’s $34 an hour, plus $23 an hour in benefits – don’t look short-term. Take the blinders off and look long-term.”

Delsman said the tides have changed between employers and employees.

“Right now, the employee has the hammer,” he said. “Ten or 15 years ago, the employer had the hammer. There are so many job opportunities right now, and companies are stretched thin. Maybe you’re single and 19 now, but what about when you’re married, want a house, a cottage or toys? When people hear about a five-year apprenticeship, it goes by like that. The training is all paid for – it’s essentially a free college education.”

In a document supplied to The Business News, the base rate pay through UA 400 for a fifth-year apprentice is $34.71 an hour.

Another $10.05 and $9.29 per hour are included for the apprentice’s pension and healthcare, respectively, which is paid for by the employer.

“If you start an apprenticeship with us, by year three, about $10 per every hour you work is put into your pension,” Delsman said. “Think about that – that’s like $1,600 per month multiplied by 12 months multiplied by 40 years, plus what you gain in interest. That number is mind boggling if you stay with it. Google a value calculator – that’s math and a real number.”

Martin said the total benefits package per hour will only go up.

“Five years from now, it might be five or 10 dollars more per hour,” he said.

Member support

Delsman said like any union, UA400 has membership dues.

Any increases in those dues, however, must be okayed by the union.

“If you look at the facility, you see part of it is under construction,” he said. “The members recently voted to spend $1 million on this place – to modernize it, update it and add classrooms.”

Delsman said UA 400 also invests more than $2 million annually in training.

//s3.amazonaws.com/appforest_uf/f1668633408483x411927638789549200/richtext_content.webpDustin Delsman

“We need to look down the road and ask the members if they’re willing to pay an additional penny or two an hour – or whatever that cost might be – to help fund things,” he said.

According to the document supplied to The Business News, a fifth-year apprentice will pay about $3 per hour in union dues to help pay administrative salaries, the cost of the addition and maintenance and upkeep.

About another $1 per hour is paid by the members to help fund UA 400’s $2 million annual training budget.

Women members

Martin acknowledges there is a stigma that the trades are not for women but said UA 400 is working to change that.

“We have female members, but we continue to work on that initiative,” he said. “Last year, we had our first-ever ‘Women in Pipefitting’ event. It was geared specifically toward attracting women into the trade. We had women speakers and stations set up in the shop run by women. Women make up 51% of the population, so why would we exclude them from our organization? You’re never going to meet your goals if you have the attitude, ‘I’m just going to hire a 6-foot, 18-year-old male who works on a farm.’”

Martin said he recently attended a national construction union event for women in Las Vegas.

“It’s easy for a 25-year-old male to go work construction, but it’s more challenging for women,” he said. “A 25-year-old female might want to have a child and must drive an hour to work every day for a construction job – it’s challenging. That’s why we’re looking at healthcare and childcare issues.”

Martin said he feels UA 400 is progressive, but it can do more.

“I know of other organizations adding on and having childcare centers right on-site so members can drop their kids off – they’re trying to remove the barriers,” he said. “We are working to get there in the future.”

Martin said of the 88 new apprentices at UA 400, six of them are women.

“I’m proud to say that – it’s a start,” he said. “In some years, the number is zero. Having six in one year says something. Our employers are recognizing it, too. They just want quality workers to fill their needs, and we’re trying to help.”

A school district’s view

Becky Walker, the associate director of college and career readiness for the Howard Suamico School District, said she works on providing opportunities for students to help prepare them for the future.

Walker said much of her time is spent with Bay Port High School students because college and career readiness programming is more prevalent there.

“I work on what students need from the district and make sure that happens,” she said. “Students need to investigate what they need to do while in high school to prepare for the future. I don’t necessarily work with students one-on-one. I work more with our programming so the counselors and teachers can provide the opportunities.”

Bay Port recently hosted a job fair, which Walker said included a lot of trade businesses, such as electrical, plumbing, cabinetry and construction.

“(Many of them) will have employees retiring in the next five or 10 years,” she said. “They’re concerned about how they’re going to replace those workers.”

Walker said she feels there has been a slight shift in the popularity of trades.

“As we engage more in youth apprenticeships with employers, we’ve had employees say, ‘If you find someone in the program doing quality work and they’re interested in continuing, we’ll pay for training,’” she said.

Walker said she’s also seeing a change in the education certain jobs require.

“I recently heard a statistic – I can’t remember where from – but only about 30% of the jobs moving forward will need a four-year degree, which means 70% won’t,” she said. “When we look at showing kids where they should go after high school, we shouldn’t be pushing so many kids to four-year degrees – unless they know for certain that’s needed for the career they’re going into. There’s nothing wrong with going for a four-year degree if that’s what they need.”

Walker said a “good number of students are making that mistake.”

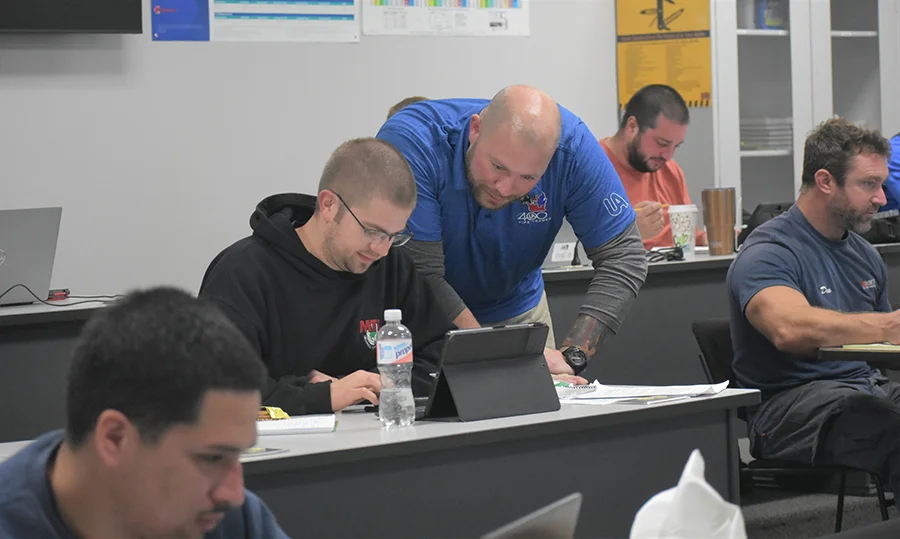

//s3.amazonaws.com/appforest_uf/f1668633449482x604517108076354300/richtext_content.webpA welding instructor at UA Local 400 listens to a student in the Kaukauna training facility. UA 400 has more than 2,400 members who supply area companies with trade workers. Rich Palzewic Photo

“If students are going to get a four-year degree just because they think that’s what they need, but don’t have any idea what they want to do with that degree, that’s not a good path to go,” she said. “It’s important that kids are exploring more in high school so when they graduate, they’re going into further education that truly prepares them for their career.”

A teacher’s view

Abe Allen, a technology and agriculture teacher at De Pere High School, recently coordinated a presentation at the school from UA 400’s youth apprentice promoter, DJ Kloida.

“Seven classes, with more than 130 students, participated in a hands-on pipefitting project,” he said. “Our material process, small engines, woods and metals classes took part. They all enjoyed having someone from the community come in with a fun project for them to complete. Students in all our classes enjoy the hands-on approach.”

Allen said both the De Pere and West De Pere school districts have continued to offer opportunities to students through their youth apprenticeship program, which they jointly hired Corey Wollins to serve as coordinator for.

Allen said the program aims to have 100 students in the program by next summer.

“I feel the administration and counselors have also changed their tune regarding the trades,” he said.

Allen said part of his district’s mission statement reads: “Provide opportunities and resources toward all pathways after high school in a global view.”

“I’m also seeing more companies willing to help kids who want to try their trades,” he said. “Sure, you can go almost anywhere now and make $15 per hour, but why not give a youth apprenticeship program a try and make $15 an hour at something that might be your future.”

Allen said Kloida also came to the school last spring and will be coming again next spring.

“DJ’s presentation is great because he has a hands-on approach,” he said. “It helps grow our programs.”

Allen said he’s a classic example of someone who didn’t think hard enough about what he wanted to do upon graduation.

“I’m a 1990 De Pere graduate and was a dairy farmer,” he said. “I received a degree from the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay in mathematics/computer science and never used it. I then went to UW-River Falls to become an agriculture teacher.”

Local artist inks contract for private studio in Appleton

Local artist inks contract for private studio in Appleton Transition of Miron leadership builds on legacy of quality, safety, family

Transition of Miron leadership builds on legacy of quality, safety, family